On March 18, 2020 the President stated that the pandemic was nothing less than a war on our own shores. Yet, there seemed to be little response from any federal agency responsible for keeping Americans safe from attack. We never got a report from the Situation Room talking about the battle, strategy, or specific metrics to know if we were winning. Were the lights in the Situation Room even turned on?

Going a step further, it would appear that the military didn’t think much about this war: there was a major battle lost on the USS Roosevelt when hundreds of its crew succumbed to COVID 19 while the Pentagon was absorbed in planning for future conflict. It would appear that we are not capable of broadening our National Security needs to include a pandemic war, only a military war. This inability to react to a predictable pandemic resulted in unheard of personal and financial loss, worse than any military conflict in 70 years. America and Americans are wounded now and it’s time to examine and then heal.

In addition to military inactions, our Strategic National Stockpile, the primary inventory backup for public healthcare emergencies, had moldy PPE and broken equipment being shipped to what has been described as “Our Front Lines” of the COVID-19 war. This was overlaid with unclear instructions about how to release the supplies within the Stockpile, informal attempts to trigger the Defense Production Act, inconsistent messaging and a campaign of finger pointing at the top of our government. And an inexcusable gap emerged: the US citizens could not trust their own government to respond to a crisis that impacted it citizens within its own shores. This “too little too late” scenario unfolded and produced a war with 50 distinct and yet connected battlefronts: with each state descending to a “Lord of the Flies” like competition for critical supplies for their front lines along with multiple local skirmishes among cities. As one elected official put it “we are all competing for the same equipment and that demand is driving the price higher and higher.” Winning a war with 50 fronts is a near impossible task.

The good news is that there was incredible ingenuity for workarounds to counter the lack of national organization and support: citizens sewing masks, engineers re-purposing other equipment to ventilators, hospitals and universities creating their own testing capabilities, and states sharing critical equipment with other states. We proudly witnessed the emergence of 21st century Minute Men: another group of true heroes in all corners of the nation who stepped up to fight a war that relies on ingenuity, not guns. But we shouldn’t confuse this with a well laid out plan: this was a reaction of a nation that was forced to respond as it had more casualties than the next worst five countries combined in the COVID-19 international war. It would seem we fought the worst battle in the world.

We need to learn from this failure and adapt quickly before the next pandemic arrives on our shores.

Learning and Looking Ahead: Producing, Distributing, and Funding

While many of our leaders are talking about learning from this disaster to create a stronger future, I’d like to suggest that part of this reflection begins by taking aim at two interconnected weaknesses in our response to this pandemic: the Defense Production Act (DPA) and the Strategic National Stockpile (SNS).

The DPA was developed for military applications and is routinely triggered to one degree or another. When “health services” was formally recognized in the DPA in 2012, it was truly a case of a square peg in a round hole. Under Title III in the current DPA, The Secretary of HHS has delegated authority over “health services,” which will get materials produced. The Secretary of Transportation has authority over domestic transportation which will move materials. The DPA was untested for health services and no one really knew how it would act until it didn’t act at all during this pandemic.

Army General John J. Pershing

The Strategic National Stockpile began in 2000 with a plan to distribute emergency health care materials in specialized bulk air cargo containers to achieve a 12-hour response in a healthcare crisis. Currently, it is operated under the Department of Homeland Security in coordination with the Secretaries of HHS and the VA. While deploying medical supplies in over 60 instances through its history, the largest recent deployment was in response to the H1N1 influenza pandemic.

In terms of its contents, there has been significant modeling of crises throughout the years and collaboration with at least 10 federal agencies resulting in many updates to the Stockpile inventory content requirements. Yet, it has lacked consistent and adequate funding to run efficiently and keep its inventory nominal. The actual plan is only physically tested during specific crises. According to a 2016 publication, the SNS crisis responses have never matched expectations. That being said, Greg Burel, then Director of the Stockpile, concluded that there was full confidence in the safety and efficacy of the products in the stockpile.

An underlying challenge with the SNS, is that it has been under-funded over the past several years, regardless of administration. The challenge being, there is discretion in the funding that falls victim to political whims. Over the course of the repeated use during the past 21 years, funding was chronically insufficient to replenish the SNS.

There are two elements of the funding, one, adequately resource the full replenishment of the SNS, two, ensure sustainable funding. To do this right we also need a way to permanently fund the inventory and the staffing required to ensure its efficacy and support the ongoing drills. There is also the need to maintain currency of the materials in the SNS. Another funding-related issue that has been revealed is a lack of methodology to manage turnover of expiring material.

The DPA and the SNS, when combined, are two elements of a conceptual supply chain, including a production/procurement system and a distribution system. But they were not designed to be formally stitched together and they both failed us as separate, unconnected systems. The DPA was not fully triggered, and what was resulted in “too little too late,” demonstrating the SNS had a broken distribution process and inventory that included moldy masks and broken ventilators. To meet the national security needs of the next pandemic we need a supply chain that is proven to respond in a way that supports our National /security interests. And it needs funding which can’t be seen as nonessential at any time.

Recommendations

The gap we now see is an unsystematic reaction to a pandemic war on our shores. This preparedness gap covers a host of weaknesses, from early identification of a potential pandemic to all aspects of our society and economy that need to be turned off, financially supported, and then turned back on. It’s time to remove “health services” from the DPA and create a comprehensive, resilient health care supply chain which incorporates producing, storing it at the SNS, and distributing it from the SNS. And do it better by constantly exercising this plan to ensure that it its operational effectiveness.

We can use the thinking the military incorporates to maintain operational effectiveness of the SNS. Our armed forces hold War Games all the time to remain prepared for different conflict scenarios. Our National Guard has frequent exercises practicing different workouts in order to be able to step in quickly where and when there is a need. Missing from our pandemic preparedness are the same deliberate drills for the pandemic war that will come again, maybe soon, to our shores.

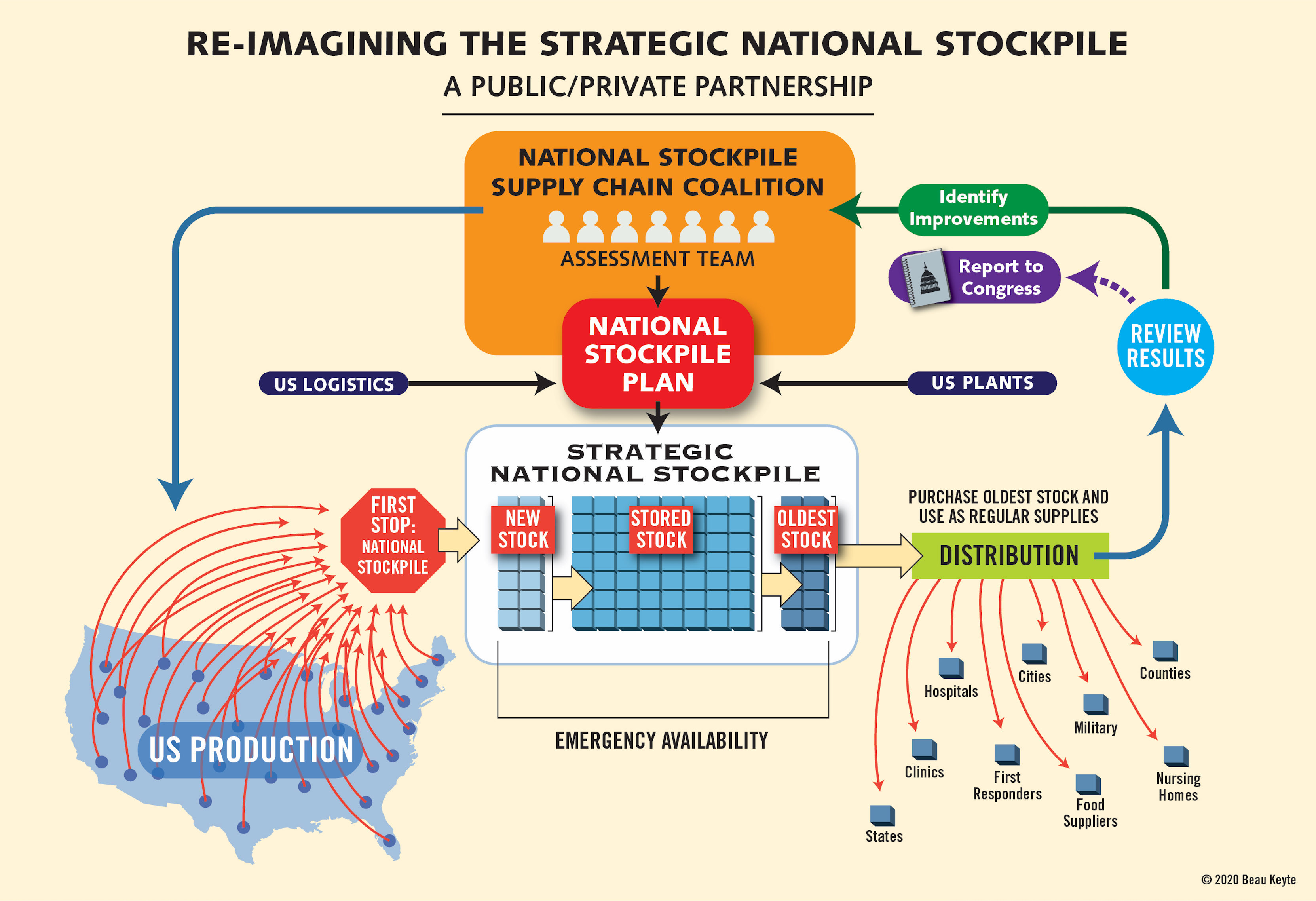

Re-imagining the Strategic National Stockpile

If we remove Health Services from Title III of the Defense Production Act, we are able to create a fully autonomous and integrated production and distribution supply chain for the Strategic National Stockpile. And, with secured funding, we can be assured that it is effective and efficient in supporting our pandemic needs.

Here are the proposed building blocks to ensure an adequate and responsive supply chain for the front lines of a healthcare crisis:

Review the results of each drill, then adjust. While the Stockpile Assessment Team can play an important role here, I recommend a review by the customers of the National Pandemic Response Coalition made up of state emergency coordinators, appointed by the governors, and the healthcare systems relying on the Stockpile to be there for them when they need it. Their feedback is critical for making constant adjustments to ensure an effective and efficient response. Given our dependency on our governors during this current crisis, and the amazing way they stepped into leadership roles, if we can convince them the system is sound they can convince the people they serve that this system can be trusted.

Funding the SNS

As noted earlier the failures seen during the pandemic relate not only to management of the strategic stockpile, but how it is funded. Over the past several administrations budget compromises resulted in an underfunding, thereby reducing the volume and quality of the supplies.

Currently the SNS funding is discretionary. Amounts are set by Congress as part of the budget for the Department of Health and Human Services. The amount of funding that is finally set is subject to routine budget negotiations, and as seen historically, is generally less that requested, or required.

We propose that the budget for the Strategic National Stockpile be set, and the funding be “lock-boxed” in a manner that allows the amount to keep current with inflation but not be funded below a minimum amount. Further, there should be a self-funding component to the budget that allows for the materials to remain current and feed funds back into purchasing more supplies.

There are a couple of current examples of how this may be designed. First, drawing form the Social Security Trust where a payroll tax is collected and appropriated to the SST with the remainder of the income coming from investment income. According to one market report, the estimated cost medical supplies in the US averages $3.9 million. Conservatively applying the average across the 5,000 US hospitals, this is $19.9 billion. Using a similar approach, to the SST, a tax would be applied to the sales of medical supplies that is then appropriated by congress similar to social security to fund the stockpile. Considering the annual HHS budget for the stockpile is approximately $560 million, this is about three percent of the estimated sales revenue of medical supplies. Because the amount of the tax is based on the value of product sold, it allows for a guard against inflationary increases.

Recognizing that the funds gathered through a tax mechanism would be used to purchase the supplies for the SNS, the option to derive revenue from investments is unlikely. This brings in the second element of funding the SNS. For this we can look to the national strategic petroleum reserves (NSPR). The NSPR not only purchases oil and natural gas, it also sells it based on supply and national need. Using a similar concept and as described above, there is a need to contemporize the materials stored in the SNS to avoid it being held past a useable expiration point. Using a first in, first out approach, stock could be rotated by placing material into a marketplace prior to it reaching a point where it will expire. Funds garnered from these sales would be kept within the budget of the SNS, in addition to the amount gathered through a strategic stockpile tax. Using this approach as a secondary funding mechanism has a dual benefit of providing revenue while keeping the stockpile current.

Both mechanisms outlined above address the ongoing support of keeping the stockpile funded. Through the past several months of the pandemic, and proceeding years of underfunding, there must also be an initial infusion of capital to bring the supply volumes up to required volumes, as well as addressing the turnover of expiring or expired materials. This infusion would most likely come in the form of a federal bolus of funds.

Moving Forward

There are indeed challenges in this sweeping effort to ensure public safety in the next major health crisis. From a process perspective, the supply chain will always be adapting to new needs in terms of either products or volumes and requires continuous evaluation of the appropriate inventory and resulting shifts in companies in the coalition. From a funding perspective, it needs to overcome the historical propensity to be ignore and sidelined in Congress: we need to keep it protected. The important point to keep in mind that we have demonstrated the deep need to constantly be ready for anything to happen in future global pandemics.

It seemed so easy to take our eyes off this need and go on with our lives as though nothing would happen. That might be true with military conflict, but not pandemic war. We now are painfully aware that we can’t rely on a political decision invoking a 70-year old Act to support a broken and moldy Stockpile. To regain the trust in the American people it’s time to be honest about our inability to fight a pandemic war and then create an effective National Pandemic Response Coalition to better serve our needs.

Let’s reimagine a nation that takes all National Security seriously and prides itself in being prepared for the next pandemic. This is the time, and all eyes are watching and waiting for such a reimagination. The critical thinking and learning involved in creating a National Pandemic Response Coalition, a National Stockpile Supply Chain Coalition, and comprehensive Pandemic War Games would prepare us for the next national response without the need for political decisions. The War of 50 Fronts should be an important lesson driving us to Build Back Better.

Beau Keyte has spent over 30 years redesigning operational systems in a variety of industries and now runs a consulting firm that advises companies on how to build new capacity with existing human resources. He is the author of “Perfecting Patient Journeys” and “The Complete Lean Enterprise.”

Sam R. Watson the Senior Vice President of Field Engagement at the Michigan Health & Hospital Association with 30 years of experience in large scale, multi-center improvement. He has published widely and spoken nationally and internationally on quality and patient safety.